Interventional oncology, practiced by interventional radiologists, is one of four parts of a multidisciplinary team approach in the treatment of cancer and cancer related disorders. The others include medical oncology, surgical oncology and radiation oncology. In general, these techniques are reserved for patients whose cancer cannot be surgically removed or effectively treated with systemic chemotherapy. These procedures are also frequently used in combination with other therapies provided by other members of the cancer team.

Therapeutic Procedures

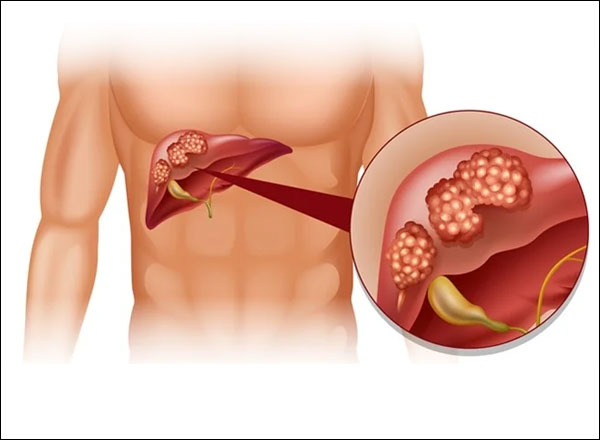

Liver cancer is the growth and spread of unhealthy cells in the liver. Cancer that starts in the liver is called primary liver cancer. Cancer that spreads to the liver from another organ is called metastatic liver cancer.

There are several risk factors for liver cancer:

- Long-term hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection are linked to liver cancer because they often lead to cirrhosis. Hepatitis B can lead to liver cancer without cirrhosis.

- Excessive alcohol use.

- Obesity and diabetes are closely associated with a type of liver abnormality called Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) that may increase the risk of liver cancer, especially in those who drink heavily or have viral hepatitis.

- Certain inherited metabolic diseases.

- Environmental exposure to aflatoxins.

Symptoms may include fatigue, bloating, pain on the right side of the upper abdomen or back and shoulder, nausea, loss of appetite, feelings of fullness, weight loss, weakness, fever, and jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and the skin).

A physical examination or imaging tests may suggest liver cancer. To confirm a diagnosis, blood tests, ultrasound tests, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and angiogram needed. Sometimes when picture remains unclear you may also need to get a liver biopsy. During a biopsy, a small piece of liver tissue is removed and studied in the lab.

A successful liver transplant will effectively cure liver cancer, but it is an option for only a small percentage of patients. Surgical resections are successful in only about one out of three cases. However, With minimally invasive Endovascular techniques; it is plausible to diagnose and biopsy lesions; treat primary or secondary malignancies using catheter based delivery of chemotherapy (chemoembolisation or selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT)) or percutaneous ablation techniques (using radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in liver.

You should consult an expert as he only can assess your problem and advise if you need to avail dedicated treatment. If you have symptoms as described above, you may meet any of the following set of doctors

- An Oncologist & Oncosurgeon who are cancer specialist

- An Interventional radiologist, who specializes in using imaging tools to see inside the body and do treatments with little or no cutting. It is important to see the right expert because it is equally important to know when to start the treatment. It is also necessary to know the right time to proceed to intervening into definite treatment to prevent complications. The technique used by Interventional radiologists are some of the most advanced and have proven to have given best results to the patient. You can connect with us for getting an advise for your problem. We will be happy to provide you guidance for the problem.

- Following are available treatment options of Liver Cancer:

Surgical treatments for HCC or secondary liver tumours

The only proven potentially curative therapy for HCC remains surgery, either liver resection or liver transplantation, and patients with a single small HCC (<5 cm) or up to three lesions <3 cm should be considered for assessment for these treatment options.

Surgical resection aims to remove a tumour together with surrounding liver tissue while preserving enough remaining liver for normal body function. This treatment offers the best prognosis for long-term survival, but unfortunately only 10-15% of patients with HCC are suitable for surgical resection. This is often due to extensive disease or poor liver function. Liver surgery in cirrhotic patients carries high morbidity and mortality. The overall recurrence rate after resection is approximately 50-60%. Liver transplantation may also be considered in any patient with cirrhosis and a small (5 cm or less single nodule or up to three lesions of 3 cm or less) HCC. Liver transplantation aims to replace the diseased liver with a cadaveric liver (from a deceased patient) or a living donor graft.

Patients with active hepatitis B virus (HBV) had a worse outlook due to HBV recurrence and were previously not considered candidates for transplantation. Effective antiviral therapy is now available and HBV positive patients with a small HCC, as defined above, can be assessed for transplantation. Hepatic resection should be considered as primary treatment in any patient with HCC and a non-cirrhotic liver (including fibrolamellar HCC – a specific subtype of HCC that tends to occur in livers without cirrhosis). Resection can be carried out in highly selected patients with cirrhosis and well preserved liver function who are unsuitable for liver transplantation. Non-surgical treatment of HCC Non-surgical therapy should be used where surgical therapy is not possible. Chemoembolisation can produce tumour necrosis (tissue death) and has been shown to affect survival in highly selected patients with good liver reserve. Chemoembolisation is also effective therapy for pain or bleeding from HCC. Radiofrequency ablation has been shown to produce necrosis (tissue death) of small HCCs. It is best suited to peripheral lesions, less than 3 cm in diameter. Systemic chemotherapy with standard agents has a poor response rate and should only be offered in the context of trials of novel agents. Hormonal therapy with Tamoxifen has shown no survival benefit in controlled trials. New drug therapies that reduce blood vessel growth (angiogenesis) in tumours have been used to some beneficial effect in advanced HCC. Sorafenib (Nexavar, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals–Onyx Pharmaceuticals) is a newer drug that has been shown to improve survival or time to radiological progression by approximately 3 months, but the drug is not readily available in the UK and is under trial awaiting further approval. Interventional radiological (IR) treatment There are three main IR treatment options:-. - Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE)

- Selective Internal Radiation Therapy (SIRT)

- Percutaneous Ablation Techniques / Radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

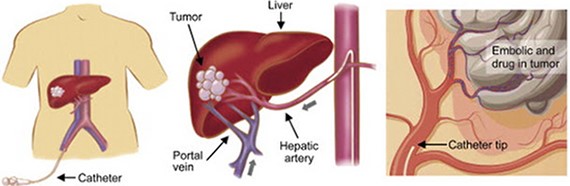

It is a localized method of administrating

chemotherapy directly to the liver tumor via a catheter. One key advantage is the chemotherapy is targeted locally so reducing the systemic side effects of intravenous chemotherapy.

A small puncture is made in blood vessel of thigh region with needle through which wire passed and sheath placed.

Angiography done with catheter under X-ray guidance to look for abnormal region of liver, once we identify the feeding vessels, catheter is placed and blocking agent placed in it.

- Why (Indications)?

- Most commonly used in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

- Selective metastatic disease (most commonly from colorectal carcinoma).

- As palliative treatment for patient with unresectable HCC or as a bridge to a liver transplant.

- Sometimes it is combined with RFA for HCC.

- Why Not (Contraindication)?

- Absolute contraindications

- Relative contraindications

- What you are to do before procedure (Preparation)?

Selective Internal Radiation Therapy (SIRT)

What is SIRT?

Both HCC and colorectal metastases are sensitive to radiation therapy (radiotherapy) but the side effects incurred from external beam radiotherapy are generally too high to tolerate. SIRT is the process of intra-arterial injection of millions of microspheres each approximately 35 microns (one-third the diameter of a strand of hair), which are bonded to yttrium-90 (Y-90), a radioactive pure beta emitter with a physical half-life of about two-and-a-half days. The microspheres become trapped in the tumour's blood supply, where they destroy the tumour by reducing blood flow and induce local radiation damage to the cellular DNA of the liver lesion. The radiation is contained within the patient's body, and is continually delivered over approximately two weeks, at which point the microspheres are no longer radioactive.

The spheres are delivered in a similar fashion to TACE via the femoral artery to the hepatic arteries and their branches.

Healthy liver tissue receives most of its blood supply via the portal vein, whilst liver tumours gain the majority of their blood supply from the hepatic artery. Therefore catheterization of the hepatic artery permits the selective targeting of therapeutic material to the tumour.

What actually happens during SIRT?

All patients should undergo baseline tumour evaluation with CT or MRI to identify tumour anatomy and the presence of complicating factors. The procedure is performed within the interventional radiology suite and under sterile conditions. The technique is performed under sedation allows the patient to feel drowsy. It is not the same as a general anaesthetic, in which the patient is unconscious.

The first part of the procedure involves puncture of the femoral artery (the main artery in the groin) after injection of local anaesthetic. A guidewire is passed up into the aorta (the main artery of the body) and then to selectively catheterise the main arteries to the liver.

A catheter is then advanced super-selectively into the tumour/s and the SIRT yttrium-90 labelled microspheres are injected into the tumour’s blood supply.

After embolisation, hepatic artery injection of radiolabelled albumin (a protein) is performed and a nuclear medicine lung scan is performed. This is to exclude the presence of significant shunting between the liver and lung circulation in which case the treatment is dangerous due to a high risk of radiation induced lung injury. If the nuclear medicine lung scan is satisfactory, then the patient returns in 1-2 weeks for administration of the yttrium-labelled spheres to the tumour via the hepatic artery. Following the procedure, the femoral puncture site is usually compressed by hand or a specialised arterial closure device may be used.

Serious complications are rare but in some patients radiation hepatitis occurs due to excessive irradiation of the normal liver, which can lead to liver failure.

Possible restrictions to the use of SIRT

SIRT may not be possible in patients who have/had: Liver failure or severely abnormal liver function tests, ascites (fluid within the abdominal cavity), previous external beam radiotherapy to the liver, treatment with capecitabine (a chemotherapy agent) within the previous two months, or if capecitabine treatment is planned within 2 months of SIRT.

SIRT is not usually undertaken if there is evidence of extensive spread of tumour outside the liver.

SIRT would not generally be undertaken in patients where the extent of cancer within the liver is amenable to surgical resection.

Percutaneous Ablation Techniques / Radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

Another route to treat primary and secondary solid organ tumours is via direct ablation (using thermal energy to destroy cells and cause tumour necrosis.) This is an evolving technique and has been used in liver, renal and lung tumours with some success.

Liver ablation techniques

Percutaneous Ethanol Injection (PEI) was an early technique involving the injection of absolute ethanol (alcohol) directly into HCC lesions under ultrasound control and achieved satisfactory results in small tumours <3cm. Other techniques that have been used include cryoablation (freezing of tumours), microwave ablation, and laser techniques, but radiofrequency ablation (RFA) remains the predominant technique.

RFA has been approved by NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence) for the treatment of unresectable HCC and colorectal hepatic metastases.

RFA – Mechanism of action

RFA produces movement of ions in the tissue which results in heating and cellular death. Heating to a temperature of 60-100°C results in almost immediate tissue damage.

RFA is based on producing tissue necrosis using a high-frequency alternating current that is delivered through an electrode placed in the centre of the tumour. Tissue necrosis begins as the temperature approaches 60°C, and RFA treatments often result in local tissue temperatures that approach or exceed 100°C, which result in tumour cell death.

It is possible to treat single tumours of up to 5 cm in diameter, and multiple tumours of <3cm diameter.

What actually happens during the procedure of RFA?

RFA may be performed either under sedation or general anaesthesia. The liver lesions will have been identified using either ultrasound (US) or computed tomography (CT), and the RFA procedure can be performed under either US or CT guidance, which is usually determined by the interventional radiologist prior to the procedure.

The procedure would normally be performed in the CT scanner or the interventional radiology suite. Once positioned upon the scanning table, the skin over the liver will be cleaned and sterilised and a sterile drape applied. Local anaesthetic is infiltrated into the overlying tissues and either sedation or general anaesthesia is required for pain relief during the procedure.

An insulated needle with an electrode at the tip is used which transmits high-frequency alternating current to the tumour tissue. The needle electrode is inserted into the tumour usually under ultrasound guidance with CT to confirm the final position.

Following ablation of the tumour, continued heating of the needle on withdrawal or “track ablation” avoids spreading of tumour cells.

RF - Ablation Tumours - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FcqAegf6q3w

Restrictions to the use of RFA

The following factors may mean that RFA cannot be performed:

Significant evidence of cancer outside the liver, invasion of bile ducts or major vessels, liver cirrhosis or active infection. Difficult to access lesions (may be sometimes necessary to perform RFA under open or laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery.)

Tumours that occupy >40% of the volume of the liver (the amount of liver left after RFA might not be sufficient to preserve liver function.)

Close distance to important structures like vessels and nearby organs.

A relative contraindication may be if lesions are larger than 5 cm.

Complications of RFA

Complications of RFA include haemorrhage, liver abscess, and heat injury to adjacent structures e.g. bowel and gallbladder. The use of “hydrodissection” (the injection of dextrose solution to push away other nearby organs) can be used to avoid local complications or injury to other structures.

Results of RFA in HCC, either alone or in combination with TACE have been encouraging.

- Regularly see a doctor who specializes in liver disease.

- Talk to your doctor about viral hepatitis prevention, including hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccinations.

- Take steps to prevent exposure to hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

- If you have cirrhosis or chronic liver disease, follow your doctor's recommendations for treatment and be screened regularly for liver cancer.

- If you are overweight or obese, diabetic, or drink heavily, talk to your doctor.

Supportive Procedures:

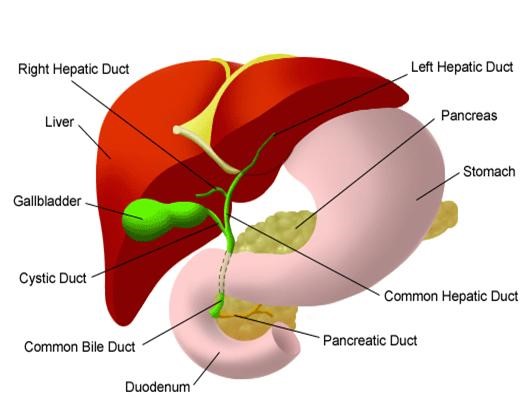

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage is a procedure where a small, flexible, plastic tube is placed through the skin into the liver in order to drain an obstructed bile duct system.

The liver produces bile which aids digestion of fats. The bile flows through a series of small tubes (ducts) that drain into one large duct called the common bile duct, which then empties into the duodenum, the first part of the small bowel after the stomach. Bile is also stored in the gallbladder.

If the bile duct becomes blocked, the bile cannot drain normally and backs up in the liver. Signs of blocked bile ducts include jaundice (yellowing of the skin), dark urine, light stools, itching, nausea and poor appetite. This is a potentially serious condition that needs to be treated. It is possible to relieve the obstruction by inserting a fine plastic drainage tube (catheter) through the skin (percutaneous) into the obstructed bile duct, past the obstruction and into the duodenum by minimal invasion.

This relieves the congestion in the blocked duct by allowing the bile to drain externally into a collecting bag as well as draining internally in the normal way.

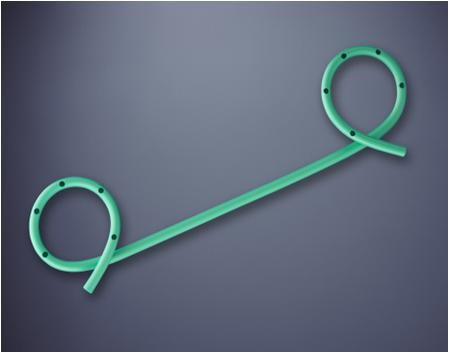

Sometimes the biliary drainage procedure needs to be extended with the placement of a permanent plastic or metal stent across the site of the bile duct blockage.

Stents are usually inserted in 2-3 days after the initial drainage procedure and they keep the narrowed duct open without the need for a catheter.

Stenting may be preceded or followed by biliary dilatation, which involves dilating a segment of bile duct with a balloon to open up the stricture.

The most common indication for biliary drainage is blockage or narrowing (stricture) of the bile ducts. There are several conditions that may cause this including:

- Gallstones – in the gallbladder or within the bile ducts

- Inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis)

- Inflammation of the bile ducts (sclerosing cholangitis)

- Tumours of the pancreas, gallbladder, bile duct, liver

- Enlarged lymph nodes in the region of the pancreas and liver due to various types of tumours

- Traumatic bile duct rupture or Injury to bile ducts during surgery.

Biliary drainage relieves obstruction by providing an alternative pathway to exit the liver.

Biliary drainage may also be necessary if a hole develops in the bile duct, resulting in leakage of bile into the abdominal cavity. This leak may cause severe pain and infection. Biliary drainage stops the leak and helps the hole in the bile duct to heal.

Biliary drainage may be necessary in preparation for surgery or other procedure on the bile ducts, such as removal of a bile duct stone or tumour.

The procedure is performed by interventional radiologists. They are doctors specializing in minimally invasive treatments using image guidance. Interventional radiologists are trained to use diagnostic imaging equipment,

such as x-ray and ultrasound, to guide various instruments during a procedure. The procedure will take place in the Interventional Radiology Department in a room especially adapted with x-ray and ultrasound equipment.

You will be taken back to your ward where your blood pressure, pulse rate, oxygen levels and temperature are monitored regularly. You will be on best rest for a few hours until you have recovered. It is important to take care of the drainage bag so that the catheter does not get pulled out. The nurses will empty the drainage bag at regular intervals and record the drainage output. If you are discharged with the catheter and bag in place, the nursing staff will teach you how to care for the catheter at home, such as how to empty the bag and change the dressing

Although biliary drainage is a relatively safe technique, there are potential risks as with any procedure. Occasionally, it may not be possible to place the drain in the bile duct, in which case surgery may be required to relieve the blockage. Sometimes the bile may leak around the catheter and form a collection in the abdomen that can cause pain and may require drainage. Occasionally, the procedure can cause a blood infection (septicaemia) but prophylactic antibiotics are given to reduce this risk. Occasionally, bleeding may be a problem that requires a blood transfusion. Rarely, bleeding can be more severe and an embolisation procedure or surgical operation may be necessary.

With regards to biliary stents, they may be misplaced at the time of the procedure or may migrate following the procedure. These can be rectified by placement of a second stent in the correct place.

We have very fast and competent working team which provide you comfortable atmosphere and ease your nerves. Usual time of stay is around 2-3 Days.

You can resume your work after 1 week if existing disease allows.