Children and adults with vascular malformations are best managed with a multidisciplinary team of specialists. Interventional radiology may deliver primary treatment such as staged sclerotherapy and embolization for malformations that are poor candidates for primary surgical resection or play a supportive role such as preoperative or intraoperative embolization. A thorough understanding of vascular morphology and flow dynamics is imperative to choosing the best treatment tool and technique.

Our minimally invasive image-guided treatments effectively treat patients with minimal discomfort.Children and adults with vascular malformations are best managed with a multidisciplinary team of specialists. Interventional radiology may deliver primary treatment such as staged sclerotherapy and embolization for malformations that are poor candidates for primary surgical resection or play a supportive role such as preoperative or intraoperative embolization. A thorough understanding of vascular morphology and flow dynamics is imperative to choosing the best treatment tool and technique.

Vascular Malformations:

A vascular malformation is an abnormal development of blood vessels. They might be found in the large arteries and veins, in smaller vessels called arterioles and venules, in microscopic capillaries, and/or in the lymphatic channels that carry lymphatic fluid and white blood cells outside of the arteries and veins.

Vascular malformations are most easily categorized based on the type(s) of vessels involved and how blood flows through them. They include the following:

- Capillary malformations, also known as port-wine stains (Venous Malformations)

- Slow-flow venous and lymphatic malformations

- Fast-flow arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and arteriovenous fistulas (AVF)

- Congenital mixed syndromes such as Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome, Parkes-Weber Syndrome, Osler-Weber-Rendu Syndrome, CLOVES syndrome, Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome, and others

Slow-flow vascular malformations include venous and lymphatic malformations.

Venous malformations:

These are the most common vascular malformations. They affect the veins, which carry blood from organs back into the heart and lungs for re-oxygenation. They can occur anywhere in the body, and they can be isolated or part of a syndrome, most commonly Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome.These venous malformations tend to be identified later in life; typically, symptoms are triggered by an injury, or physiological changes such as puberty or pregnancy. Sometimes they are found incidentally, during MRI studies for other conditions. Symptoms suggesting a possible venous malformation range from minor aches and pains to recurrent bouts of bleeding, clotting disorders and organ damage, mostly within bones, joints and skeletal muscles.

Lymphatic Malformations:

The lymphatic vessels carry lymphatic fluid and white blood cells outside of the arteries and veins. Malformations affecting the lymphatic channels may start to cause problems during infancy and early childhood. They can cause pooling of the lymph fluid into cysts or fluid-filled pockets of various sizes. These cysts, in turn, can develop problems such as infection, bleeding and erosion into adjacent organs.

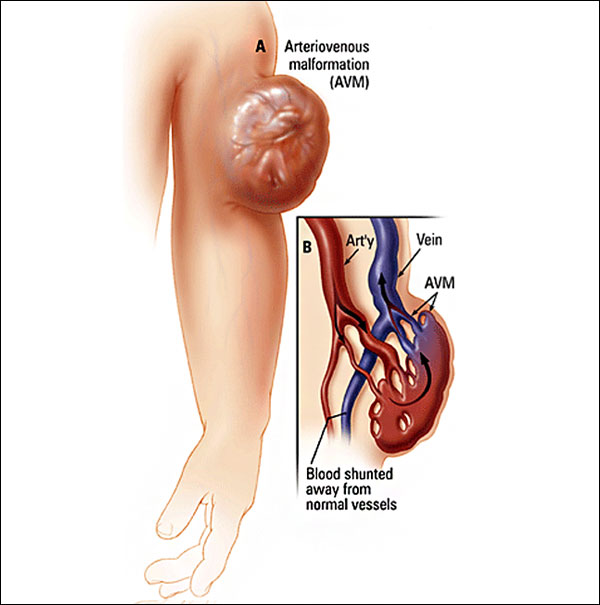

Fast-flow arteriovenous malformations develop as the result of an abnormal connection between arteries that supply the body’s organs, and the veins, which drain them. Picture these as being like short-circuits: Blood pumped from the heart to a given organ can’t get there and is instead sent back toward the heart. The draining veins become dilated and engorged, the target organ is deprived of needed oxygen and nutrients, and–in the worst scenarios—heart and/or organ failure can develop

Arteriovenous malformations can occur anywhere in the body, but are most typically found in the brain, spinal cord and extremities. It is rare, but possible, for arteriovenous malformations to be found in the internal organs, including the kidneys, the intestines and the lungs. While there is currently no cure for arteriovenous malformations, various treatment options exist aimed at slowing their growth, and minimizing and at times eliminating symptoms.

There are several congenital mixed syndromes that involve vascular malformations.

- Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome (KTS): This syndrome is diagnosed if two the following three criteria are present: port-wine stains, bony and/or soft tissue overgrowth, slow-flow venous/lymphatic malformations. The venous malformations in KTS can be quite extensive and involve bones, joints and muscles, as well as the skin and the underlying fat. There is an increased risk of recurrent infections, as well as clotting in the veins.

- Parkes-Weber Syndrome: This is very similar to Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome, except that it involves high-flow arteriovenous malformations associated with an arm or leg.

- Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome: Also known as Bean Syndrome, this refers to the presence of multiple, isolated slow-flow venous malformations on the skin and in underlying tissue, as well as in the intestines and other internal organs.

- CLOVES (congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, epidermal nevi and spine deformities): This condition, which affects infants and young children, features fatty tissue overgrowth throughout the body. It commonly affects the trunk, feet and limbs, head or neck. Some children have a deep red (purplish) rash that looks something like a port-wine stain. People with CLOVES may have spinal deformities such as scoliosis and high-flow arteriovenous malformations that affect the spinal cord.

- Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasias (HHT): Also known as Osler-Webe-Rendu Syndrome, this condition (passed by parents to children) is marked by malformations of small-end arteries. The symptoms include multiple nosebleeds and skin rashes, particularly on the palms of the hands and feet. Getting proper treatment is vital to prevent clots from traveling to the brain.

Your doctor will have a suspicion or a good indication that you have an AVM on the basis of the history you provide and on physical examination or in some circumstance your family history. Your doctor will refer you to a Endovascular Interventional Radiologist who are recommended specialist.

The diagnosis is typically clinical and imaging the lesion is key to understand the size and nature of the lesion. Imaging can also help decide when and how to treat these lesions. Ideally AVMs should be managed by a ‘multi-disciplinary’ team of doctors, nurses and specialists with a specific interest and experience in diagnosing and treating this condition.

- Ultrasound: This is a test that uses sound waves to detect abnormalities and is particularly good at showing flow of blood as it a dynamic and non-invasive investigation. This test will help to determine the flow characteristics of the lesion but will not give a detailed anatomical picture of the problem.

- CT scan: This a non-invasive X-ray test that allows the radiologist to see the body in slices on a computer screen. An injection of special ‘dye’ called ‘contrast’ is used at the same time to highlight blood vessels and this is sometimes called a CT Angiogram. These images can then be manipulated on a computer and give a detailed 3-D picture of the AVM and allow management planning.

- MRI scan: This is similar to a CT scan but uses magnetic fields instead of radiation. Often MRI gives more detailed anatomical information especially in the brain.

- Angiography: This is a more invasive investigation that involves the introduction of a small, narrow plastic tube into the blood vessels called a catheter. This is usually carried out using local anaesthetic. The catheter is placed typically in the artery in the groin called the femoral artery. A picture of the blood vessels can be obtained by injecting dye (contrast) through the catheter using an X ray machine. This gives detailed information to the nature and anatomy of the blood vessels making up the AVM. This test is not always necessary nowadays as CT and MRI scanning offers similar accuracy. Angiography is usually carried out at the same time as treatment or occasionally if CT or MRI findings are indeterminate.

AVMs are very complicated. It is important that treatment and follow up is carried out and supervised by an endovascular interventional Radiologist team.

Treatment options range from endovascular therapy to Surgery to Endovascular therapy.

This is defined as the intentional occlusion of the blood vessels that make up the AVM. This is carried out in conjunction with an angiogram (see earlier). Depending on the embolisation agent and access technique used by the Interventional Radiologists a general anaesthetic may be required.

Embolisation of these lesions typically involves one of two techniques:

- Percutaneous direct stick and direct instillation of embolic material into the nidus of the AVM.

- Endovascular transcatheter embolisation. This is very similar to the angiogram you will have had but often involves using more specialised catheters and guidewires. The embolic material is then delivered via the catheter. An arterial or venous approach can be used.

There are a number of embolic materials used. The interventional radiologist will discuss these with you. They range from liquids (sodium tetradecyl sulphate STD, alcohol, histoacryl glue and Onyx), metal springs (coils) or metal plugs that block the blood vessels in this region. - Figure: Traumatic AVM of the lip. Angiogram demonstrating the typical appearances treated with glue embolisation and the resultant cessation of blood flow.

Treatment can be curative, but more often is palliative, in that it is to reduce potentially life threatening complications and down grade the AVM. Simple AVMs maybe treatment successfully in a single session but the majority require more than one treatment session is required over a period of time - Surgery

Surgical resection of AVMs can be appropriate is some cases but is fraught with danger as these lesions can bleed significantly at surgery. Surgery can also be quite disfiguring and even lead to functional impairment. AVMs can often recur after surgery.

That’s not to say there is no place for surgery in the management of AVMs. Often surgery and embolisation are complimentary where the lesion is first de-vascularised (blood supply reduced) by embolisation and then surgery performed to remove the residual AVM with limited blood loss at the time of the operation.

Treatment options are divided up in to conservative management, percutaneous injections (Sclerotherapy) or surgery or a combination of these. If there are no symptoms then there is no indication or need for treatment.

Initially it important to determine the exact symptoms and to what degree this is distressing the patient and how much of an impact this is having on their life. The majority of venous malformations do not need treatment, but this can be reviewed at any time, especially if symptoms worsen or change. Venous malformations are not malignant and do not have malignant potential.

Conservative management includes pain relief with anti-inflammatory tablets, compression dressings if the lesion is in a limb and alteration of lifestyle accordingly. This approach is usually advised if symptoms are well tolerated.

Treatment depends on the number of vascular spaces within the lesion and the amount of more solid tissue. Lesions with a more spacious component (ie: more venous lakes) are more suitable for injection therapy or ‘sclerotherapy’ than those that are predominantly solid in nature. Depending on the site, size amongst other factors certain lesions are suitable for surgical removal.

Sclerotherapy is a type of treatment that involves the injection of a special chemical into the venous malformation to ultimately shrink it and relieve the symptoms it is causing. Various substances can be used but most commonly the chemical used is Sodium Tetradecyl sulphate (Fibrovein). When injected into a lesion it causes an inflammatory reaction which leads to localised blood clots and the formation of a scar in place of the venous malformation. This corresponds to shrinkage of the malformation. This is carried out under ultrasound and x-ray control as the doctor needs to be sure that the correct part of the malformation is accessed with the needle and needs to assess the degree of communication with adjacent communicating veins.

Often a ‘course’ of multiple injections are required to adequately treat a venous malformation and it can be some time before the patient notices a significant difference. Not all venous malformations are successfully treated in this way but in the vast majority of cases significant results are achieved.

It is typically carried out as a day case procedure in hospital.

Immediately after the injection considerable swelling can occur along with pain. This usually settles within days – weeks of the injection. Pain is usually adequately treated with oral pain killers. It is when this swelling settles that there is a noticeable reduction in the size and / or symptoms of the malformation.

There is a small risk of infection and bleeding but as sclerotherapy is carried out via a needle puncture and not an incision this is unusual.

Bleomycin is widely used as a chemotherapy agent to treat certain types of cancer. Vascular anomalies are not cancers but bleomycin has been shown to be effective in treating certain types of vascular anomalies when injected directly into the lesion, rather than into the bloodstream as with chemotherapy. Subtypes of vascular anomalies successfully treated include, lymphatic malformations (macro and microcystic) and even venous malformations. Bleomycin works by exerting its effect on the lining of the malformation and preventing further growth and promoting regression. It does this by inhibiting local DNA synthesis. Results are encouraging with its use. This form of treatment often requires a course of injections over a period of months. Bleomycin treatment is considered in a multi-disciplinary setting following discussion with the patient and review of cross-sectional imaging. It can be considered as a first line treatment in micro-cystic lymphatic disease.

Very small risk of bleeding and bruising at the puncture site and infection along with a small risk of damaging the blood vessels as the catheter is advanced.

Pain is often encountered following the procedure but this is usually short-lived and may last a few days.

Swelling is sometimes experienced at the site of treatment and is related to the local inflammatory process caused by blocking the blood vessels and sometimes by the embolic agent itself.

The risks will be discussed with you prior to any procedure but are generally low as embolisation is proven as a safe and effective method of treating AVMs worldwide

We have very fast and competent working team which provide you comfortable atmosphere and ease your nerves. Usual time is day care.

Resume to work?

You can resume your work very next day of the procedure preferably in 2- 3 days.